AJAM

Systemic Shifts, Local Gestures

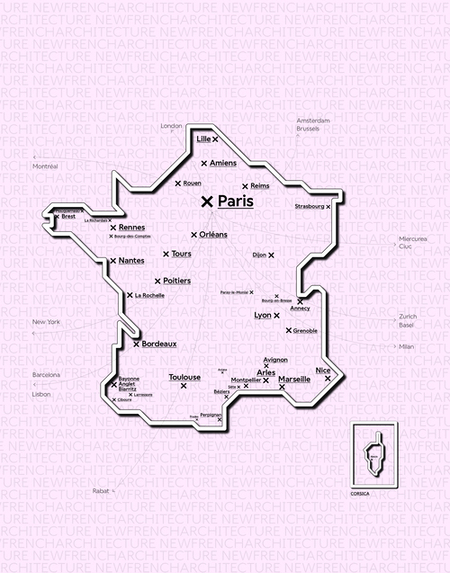

New French Architecture

An Original Idea by New Generations

Mallet Morales

Stories in Structure

Studio SAME

Charting Change with Ambition

Atelier

Coming Soon

Lafayette

Envisioning the City of Tomorrow

Belval & Parquet Architectes

Living and Building Differently

127af

Redefining the Common

HEROS Architecture

From Stone to Structure

Carriere Didier Gazeau

Lessons from Heritage

a-platz

Bridging Cultures, Shaping Ideas

Rodaa

Practicing Across Contexts

Urbastudio

Interconnecting Scales, Communities, and Values

Oglo

Designing for Care

Figura

Figures of Transformation

COVE Architectes

Awakening Dormant Spaces

Graal

Understanding Economic Dynamics at the Core

ZW/A

United Voices, Stronger Impacts

A6A

Building a Reference Practice for All

BERENICE CURT ARCHITECTURE

Crossing Design Boundaries

studio mäc

Bridging Theory and Practice

studio mäc

Bridging Theory and Practice

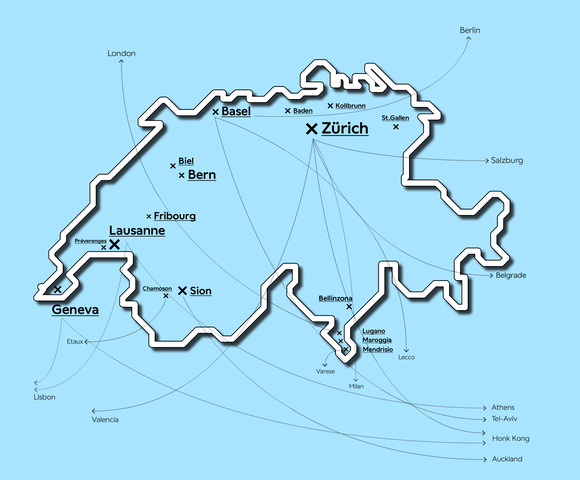

New Swiss Architecture

An Original Idea by New Generations

KUMMER/SCHIESS

Compete, Explore, Experiment

ALIAS

Stories Beyond the Surface

sumcrap.

Connected to Place

BUREAU/D

From Observation to Action

STUDIO ROMANO TIEDJE

Lessons in Transformation

Ruumfabrigg Architekten

From Countryside to Lasting Heritage

Kollektiv Marudo

Negotiating Built Realities

Studio Barrus

Starting byChance,Growing Through Principles

dorsa + 820

Between Fiction and Reality

S2L Landschaftsarchitektur

Public Spaces That Transform

DER

Designing Within Local Realities

Marginalia

Change from the Margins

En-Dehors

Shaping a Living and Flexible Ecosystem

lablab

A Lab for Growing Ideas

Soares Jaquier

Daring to Experiment

Sara Gelibter Architecte

Journey to Belonging

TEN (X)

A New Kind of Design Institute

DF_DC

Synergy in Practice: Evolving Together

GRILLO VASIU

Exploring Living, Embracing Cultures

Studio — Alberto Figuccio

From Competitions to Realised Visions

Mentha Walther Architekten

Carefully Constructed

Stefan Wuelser +

Optimistic Rationalism: Design Beyond the Expected

BUREAU

A Practice Built on Questions

camponovo baumgartner

Flexible Frameworks, Unique Results

MAR ATELIER

Exploring the Fringes of Architecture

bach mühle fuchs

Constantly Aiming To Improve the Environment

NOSU Architekten GmbH

Building an Office from Competitions

BALISSAT KAÇANI

Challenging Typologies, Embracing Realities

Piertzovanis Toews

Crafted by Conception, Tailored to Measure

BothAnd

Fostering Collaboration and Openness

Atelier ORA

Building with Passion and Purpose

Atelier Hobiger Feichtner

Building with Sustainability in Mind

CAMPOPIANO.architetti

Architecture That Stays True to Itself

STUDIO PEZ

The Power of Evolving Ideas

Architecture Land Initiative

Architecture Across Scales

ellipsearchitecture

Humble Leanings, Cyclical Processes

Sophie Hamer Architect

Balancing History and Innovation

Argemí Bufano Architectes

Competitions as a Catalyst for Innovation

continentale

A Polychrome Revival

valsangiacomoboschetti

Building With What Remains

Oliver Christen Architekten

Framework for an Evolving Practice

MMXVI

Synergy in Practice

Balancing Roles and Ideas

studio 812

A Reflective Approach to

Fast-Growing Opportunities

STUDIO4

The Journey of STUDIO4

Holzhausen Zweifel Architekten

Shaping the Everyday

berset bruggisser

Architecture Rooted in Place

berset bruggisser

Architecture Rooted in Place

JBA - Joud Beaudoin Architectes

New Frontiers in Materiality

vizo Architekten

From Questions to Vision

Atelier NU

Prototypes of Practice

Atelier Tau

Architecture as a Form of Questioning

alexandro fotakis architecture

Embracing Context and Continuity

Atelier Anachron

Engaging with Complexity

studio jo.na

Transforming Rural Switzerland

guy barreto architects

Designing for Others, Answers Over Uniqueness

Concrete and the Woods

Building on Planet Earth

bureaumilieux

What is innovation?

apropå

A Sustainable and Frugal Practice

Massimo Frasson Architetto

Finding Clarity in Complex Projects

Studio David Klemmer

Binary Operations

Caterina Viguera Studio

Immersing in New Forms of Architecture

r2a architectes

Local Insights, Fresh Perspectives

HertelTan

Timeless Perspectives in Architecture

That Belongs

Nicolas de Courten

A Pragmatic Vision for Change

Atelier OLOS

Balance Between Nature and Built Environment

Associati

‘Cheap but intense’: The Associati Way

emixi architectes

Reconnecting Architecture with Craft

baraki architects&engineers

From Leftovers to Opportunities

DARE Architects

Material Matters: from Earth to Innovation

KOMPIS ARCHITECTES

Building from the Ground Up

Fill this form to have the opportunity to join the New Generations platform: submissions will be reviewed on a daily-basis, and the most innovative practices will have the chance to be part of the media's coverage and participate in our cultural agenda, including events, research projects, workshops, exhibitions and publications.

What is your name or office's name?

New Generations is a European platform that investigates the changes in the architectural profession ever since the economic crisis of 2008. We analyse the most innovative emerging practices at the European level, providing a new space for the exchange of knowledge and confrontation, theory, and production.

Since 2013, we have involved more than 3.000 practices from more than 50 countries in our cultural agenda, such as festivals, exhibitions, open calls, video-interviews, workshops, and experimental formats. We aim to offer a unique space where emerging architects could meet, exchange ideas, get inspired, and collaborate.

A project by Itinerant Office

Within the cultural agenda of New Generations

Editor in chief Gianpiero Venturini

Team Akshid Rajendran, Ilaria Donadel, Bianca Grilli

If you have any questions, need further information, if you'd like to share with us a job offer, or just want to say hello please, don't hesitate to contact us by filling up this form. If you are interested in becoming part of the New Generations network, please fill in the specific survey at the 'join the platform' section.

➡️

➡️

➡️

➡️  ➡️

➡️  ➡️ Casa Romerillo, render.

➡️ Casa Romerillo, render.  ➡️ Casa Valles, interior render.

➡️ Casa Valles, interior render.