Fill this form to have the opportunity to join the New Generations platform: submissions will be reviewed on a daily-basis, and the most innovative practices will have the chance to be part of the media's coverage and participate in our cultural agenda, including events, research projects, workshops, exhibitions and publications.

What is your name or office's name?

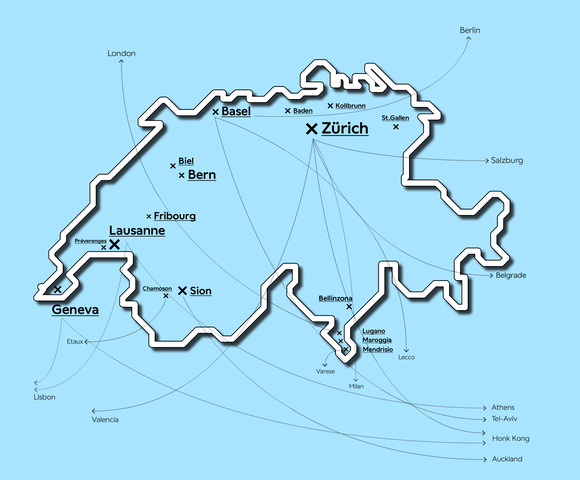

New Generations is a European platform that investigates the changes in the architectural profession ever since the economic crisis of 2008. We analyse the most innovative emerging practices at the European level, providing a new space for the exchange of knowledge and confrontation, theory, and production.

Since 2013, we have involved more than 3.000 practices from more than 50 countries in our cultural agenda, such as festivals, exhibitions, open calls, video-interviews, workshops, and experimental formats. We aim to offer a unique space where emerging architects could meet, exchange ideas, get inspired, and collaborate.

A project by Itinerant Office

Within the cultural agenda of New Generations

Editor in chief Gianpiero Venturini

Team Akshid Rajendran, Ilaria Donadel, Bianca Grilli

If you have any questions, need further information, if you'd like to share with us a job offer, or just want to say hello please, don't hesitate to contact us by filling up this form. If you are interested in becoming part of the New Generations network, please fill in the specific survey at the 'join the platform' section.

➡️ Alice Gras, Delphine Bugaud, Co-founders of DARE. Ph. credit: Valérie Pinauda

➡️ Alice Gras, Delphine Bugaud, Co-founders of DARE. Ph. credit: Valérie Pinauda ➡️ House in Ayent, 2022, burnt wooden house for a young couple. Ph. credit: Gianluca Colla – Colla images

➡️ House in Ayent, 2022, burnt wooden house for a young couple. Ph. credit: Gianluca Colla – Colla images ➡️ House in Arbaz, 2024, wooden house for a young couple. Ph. credit: Nicolas Sedlatchek

➡️ House in Arbaz, 2024, wooden house for a young couple. Ph. credit: Nicolas Sedlatchek ➡️ House in Arbaz, 2024, wooden house for a young couple. Ph. credit: Nicolas Sedlatchek

➡️ House in Arbaz, 2024, wooden house for a young couple. Ph. credit: Nicolas Sedlatchek ➡️ TERREAU, Competition for a nursery in Saillon, 2

➡️ TERREAU, Competition for a nursery in Saillon, 2 ➡️ LA GRANDE MAISON, Competition, Foyer St.Raphaël (Sion), 3

➡️ LA GRANDE MAISON, Competition, Foyer St.Raphaël (Sion), 3 ➡️ Observatory & amphitheater, 2020, burnt wood cabin. Festival des cabanes. Ph: Alexandra Filliard

➡️ Observatory & amphitheater, 2020, burnt wood cabin. Festival des cabanes. Ph: Alexandra Filliard ➡️ Rammed-Earth workshop, 2019. Ph. Credit: BC Materials, Dieter Van Caneghem

➡️ Rammed-Earth workshop, 2019. Ph. Credit: BC Materials, Dieter Van Caneghem